what was the code name for the secret project to develop an atomic bomb?

What was the Manhattan Project?

The Manhattan Project, which took place during Earth State of war Two, was a U.South. government-run endeavor to research, build, and and so use an atomic bomb. Mobilizing thousands of scientists worldwide and taking place across multiple continents, the project eventually resulted in the construction of the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

How the project got started

In 1939, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt received a letter from physicist Albert Einstein with an urgent bulletin: Physicists had recently discovered that the element uranium could generate vast amounts of free energy — plenty, mayhap, for a bomb. Einstein suspected that Hitler might already be working to stockpile the element.

Related: Einstein letter warns of German anti-semitism 10 years before Nazi'due south rise to power

Earth War 2 had barely begun, and it would be three more years before the United states got involved, but Einstein'southward letter mobilized action. The U.S. government began to marshall top physicists in a underground project. At outset, their goal was simply to find out whether an atomic flop — a weapon harnessing the free energy released past an atom separate in two — was really possible, said Alex Wellerstein, a science historian at Stevens Institute of Applied science in New Jersey. Simply by 1942, the goal was to build a bomb before Germany could. Past the time the Usa entered World War Two, the project was recruiting tens of thousands of scientists and civilians. Not long after, information technology was given the code proper noun "the Manhattan Projection."

The project's leaders

Nuclear weapons enquiry began earlier U.Due south. interest in World War Ii. Only the Manhattan Project was different from the research projects that preceded it, Wellerstein said. Earlier inquiry had been theoretical; the goal of the Manhattan Project was to build a bomb that could be used in the state of war. The project didn't truly get started until the fall of 1941, when engineer Vannevar Bush, who spearheaded nuclear research as the head of the U.Due south. authorities-backed Uranium Committee, convinced Roosevelt that the atom bomb was possible and could be completed within a year, Wellerstein said.

Within a twelvemonth, Gen. Leslie R. Groves from the U.Southward. Army Corps of Engineers was appointed as the project'south manager. That appointment was a game changer, Wellerstein said.

"He was personally responsible for making sure it [the Manhattan Project] was the number ane priority during the war. It got all the funding, all the resources. He was relentless," Wellerstein said. "If he hadn't been in charge, so it probably wouldn't accept gotten done."

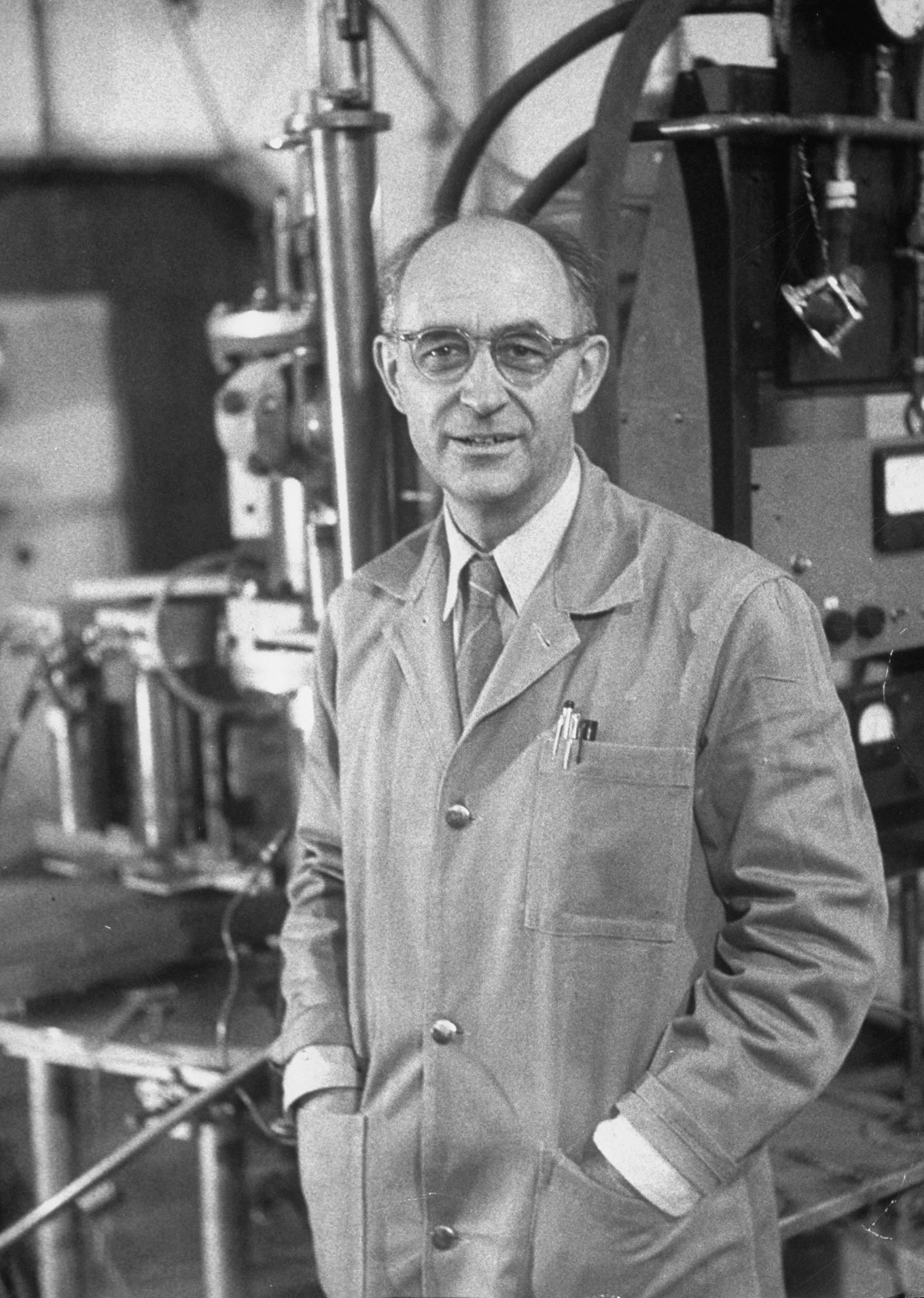

The Manhattan Project enlisted the assist of thousands of scientists across the country. Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard, physicists at the Academy of Chicago, were particularly important in the effort, Wellerstein said.

"Fermi was unusually talented at both the theory and practice of physics. That'due south unusual, even at present," Wellerstein said.

These scientists all worked nether J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Projection'southward scientific director and leader of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

One of the first steps of the project was to produce a concatenation reaction — a cascade of splitting atoms that can release enough free energy to trigger an explosion. Not long subsequently the Manhattan Projection began, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard became the first scientists in the world to achieve that goal, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

Secret cities

Despite its name, research for the Manhattan Project took place across the United States, besides as Canada, England, the Belgian Congo and parts of the South Pacific. Simply the nearly sensitive research questions were explored at Los Alamos National Laboratory, "in the center of nowhere," Wellerstein said. The laboratory, located in the remote mountains of northern New Mexico, was established in 1943.

Los Alamos wasn't the only laboratory involved in the Manhattan Project. The Met Lab at the Academy of Chicago and the Rad Lab at the University of California, Berkeley both had important roles. The questions investigated by these academy laboratories could easily exist portrayed as relating to some other application of physics, and not necessarily flop development, Wellerstein said.

Related: Bout surreptitious WWII lab with Manhattan Project app

"If you're at these other sites, y'all're making plutonium; you lot don't know why you lot're making plutonium," Wellerstein said. "At Los Alamos, you're making atomic bombs," and that was something the U.South. government needed to go on under wraps.

Los Alamos' remote location was crucial in keeping the purpose of the projection a secret. Questions explored at Los Alamos included how to physically construct a flop, how to design it, and where to put it together — "really practical, physical stuff," Wellerstein said.

To build a bomb, scientists needed large amounts of unstable, radioactive uranium or plutonium. Uranium was easier to obtain than plutonium just scientists thought that plutonium might provide a quicker road to developing the bomb, according to the Section of Energy. They decided to attempt both and built nuclear reactors for each element — the Oak Ridge uranium reactor in eastern Tennessee and the Hanford plutonium reactor in Washington.

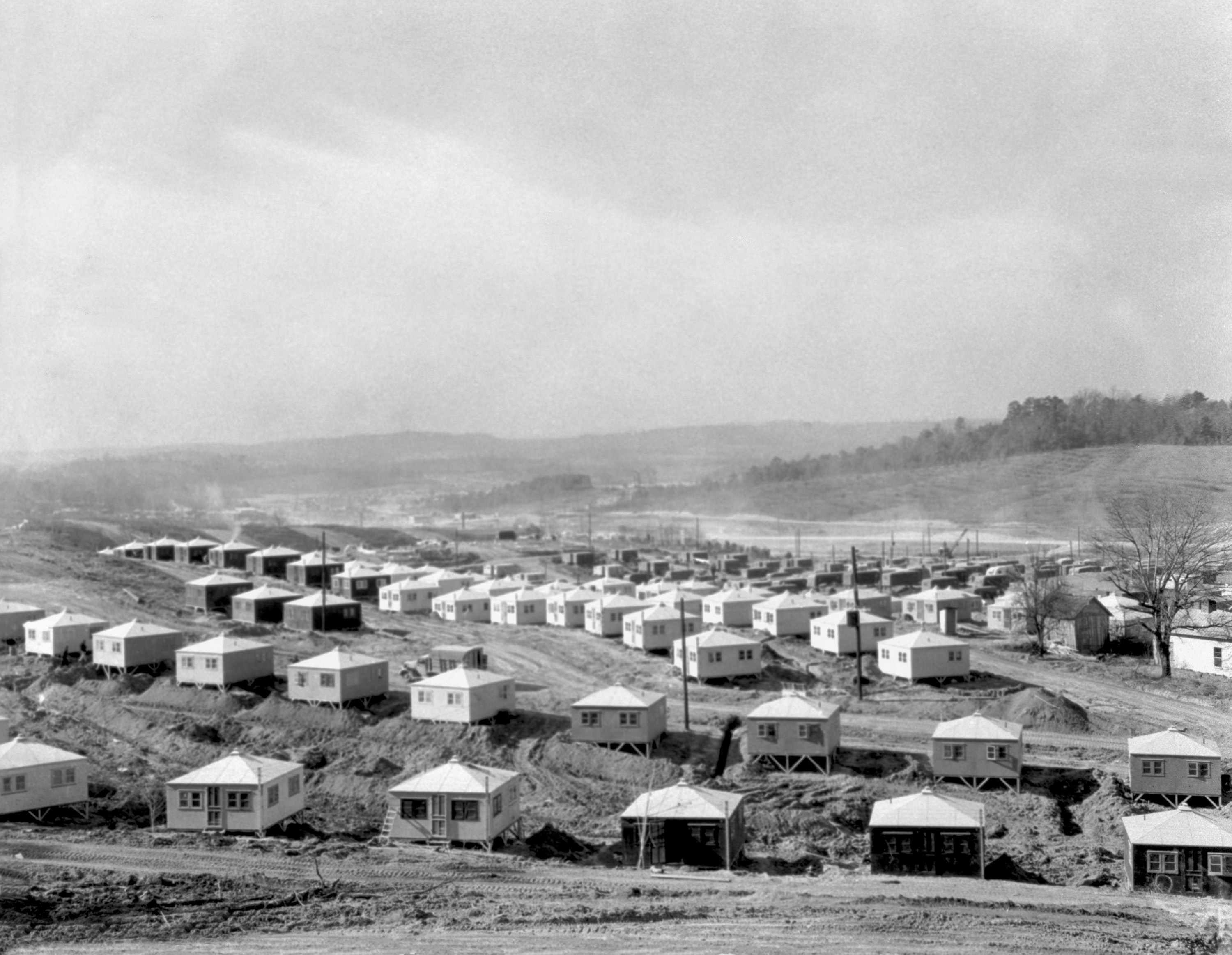

It took tens of thousands of people to build and operate these facilities: scientists, custodial staff, secretaries and administrative workers. By the end of the state of war, over 500,000 people had worked on the project, Wellerstein said. That created a claiming: How exercise you apply tens of thousands of people for an performance, all the while managing to keep that functioning a hole-and-corner? The reply was secret cities.

Cities were constructed around the new reactors to firm workers and their families. By the end of the war, Oak Ridge boasted a population of 75,000 and Hanford a population of fifty,000, according to the Diminutive Heritage Foundation. Only these cities didn't appear on maps, and most workers had no idea what they were working on, according to Voices of the Manhattan Projection, an oral history project run by the Los Alamos Historical Society. In a policy chosen compartmentalization, workers were given information on a "demand to know basis," Wellerstein said.

"It was very hard," he said. "It wasn't easy to keep a surreptitious. They had leaks and rumors and spies."

Despite how challenging it was to keep the project a undercover, the being of an atom bomb all the same came as a surprise to nearly everyone in the world, including those who had worked on it, Wellerstein said.

Using the bomb

By July 16, 1945, the first cantlet flop, chosen the Gadget, was ready. About 150 miles outside of Los Alamos, in the remote Jornada Del Muerto Desert, researchers conducted the Trinity test — the first atomic explosion.

In the years since its outset, the aims for the Manhattan Project had inverse drastically. No longer was the goal of the projection to race Germany to build a bomb, Wellerstein said. It had long been clear that Germany had no idea information technology was in a race. Instead, the U.S. government'south sights had turned to Nippon.

Soon later on the Trinity test, ii diminutive bombs, a uranium bomb called "Little Male child" and a plutonium bomb chosen "Fat Man," were assembled on Tinian Island in the Southward Pacific, and bombers began conducting test flights to Japan.

Weeks later on the explosion of the Gadget, two atom bombs were dropped on Japan. On Aug. six, 1945, Little Male child was dropped on Hiroshima. Merely three days later, on Aug. 9, Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. Effectually 110,000 people died in the initial blasts, according to the Department of Free energy. Less than one week later, Japan surrendered to the Allied forces, initiating the end of Globe War II.

Aftermath and finish of the Manhattan Project

Was the Manhattan Project a success? It depends on whom you lot ask.

Some scientists were disquisitional of the management the Manhattan Project took, Wellerstein said. These scientists liked the idea of racing against Germany to build the bomb, only had qualms well-nigh really using it. Szilard was one of those dissenters. Before Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he had petitioned Truman to not drop the bomb on a city. After the terminate of the Manhattan Projection, he quit studying physics and went into biology.

Some scientists who worked on the bomb earnestly believed that the threat of total destruction would bring an end to all state of war, Wellerstein said. By that measure, it was a failure, he said. The development of the atom bomb ushered in a nuclear arms race and the Cold War.

Still, the Manhattan Projection achieved one goal: It helped bring Globe War II to an end.

Additional resource:

- Read virtually the women who worked on the Manhattan Projection, from the U.South. Department of Energy.

- Learn more about the Manhattan Project from the Encyclopedia of the History of Science.

- Sentry this video of the Trinity test, from the Diminutive Heritage Foundation.

geisslerilthaddly.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.livescience.com/manhattan-project.html

0 Response to "what was the code name for the secret project to develop an atomic bomb?"

Post a Comment